How Can Forests Cool the Planet? They Work As Heat Pumps!

Understanding the biophysical mechanism that forests use to cool the Earth

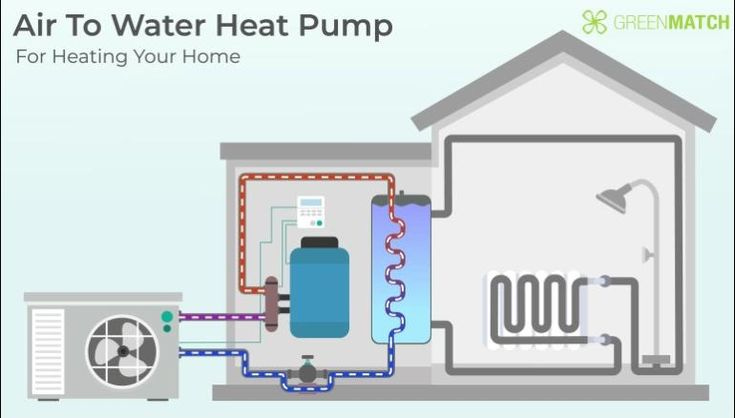

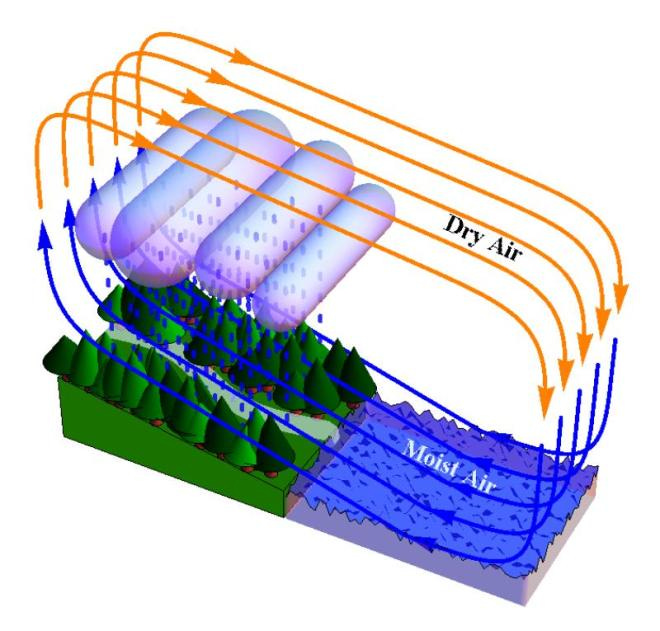

Forests cool the Earth using a mechanism similar to that of human-made heat pumps. Image from bioticpump.com

These days, everyone seems to be talking about heat pumps for homes even though, in my experience, not many people seem to understand how they work. Some people seem to think that heat pumps disprove the first principle of thermodynamics, while others think that they are an evil plot by governments to have us freeze in winter.

But heat pumps do not go against physics, and they are not so difficult to understand, and they are ubiquitous in the world around us, for instance, in the form of your refrigerator and your AC unit. There are many more instances in the ecosphere where heat is pumped from one place to the other. You are a heat pump yourself when you sweat, and forests are huge heat pumps that cool the whole planet. But let’s start from the basics.

First, you know that heat is spontaneously transferred from hotter bodies to colder ones. This has to do with the “zeroth principle” of thermodynamics, but it is pretty normal in our everyday experience. Heat spontaneously moves following temperature differences. So, what devilish trick may make it move from a cold body to a warm one? It has to do with phase transitions and with the great lady who rules the universe, Madame Entropy, or the second principle of thermodynamics.

It may be pretty simple. Consider what happens when you sweat. You exploit a phase transition to turn liquid water into water vapor, which evaporates from your skin. When that happens, entropy increases, so it is a spontaneous process. If you like, you can say that water vapor is more “disordered” than liquid water, but be careful because this is not really correct. In any case, you are pumping heat away from your body, so you cool down.

Note that cooling by sweating does nothing against the conservation of energy, the first law of thermodynamics. Energy in the form of heat is not created or destroyed; it is just moved away from your body. The water vapor you emit will just condense somewhere, releasing the heat your body produces there. But that won’t re-warm you, as you need in order to control your body temperature.

A mechanical heat pump is the same in thermodynamic terms; it just does not use water but other kinds of fluids that evaporate at lower temperatures. And, unlike sweating, it goes through an internal cycle of warming and cooling. Here is how it works (image from Wikipedia)

In the figure, red stands for “hot” and blue for “cold.” The liquid absorbs heat from B when it evaporates (just like sweat does), then it returns this heat to A when it is compressed and returned to a liquid form in the unit labeled “4”. The arrows indicate that heat is moved from B to A and from A to the environment. It is the way your refrigerator works: the refrigerator is B, and your kitchen is A. If you have a heat pump to warm your home, then B is your garden, and A is your living room.

Now, let’s go to forests and how they cool the planet. You could say that forests “sweat,” that is, they pump water vapor from their leaves into the atmosphere — it is called “transpiration” or “evapotranspiration.” All plants do that, but forests do that massively. It is not that they “want” to cool themselves; plants have no thermal regulation system akin to that of birds and mammals. They do have some thermoregulation capabilities, but they are very limited. In plants, water evaporation at the leaves creates a depression that pumps water up from the roots to the leaves. They have to use this method because they have no muscles and, hence, no hearts to pump fluids inside their bodies.

Think that some trees reach over 100 meters in height, and you can understand that they need to evapotranspirate a lot. Not only that, but trees also emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the form of small particles that favor the nucleation of water droplets and hence create clouds.

Now, there comes the heat pump mechanism. Because of the work of Madame Entropy, evapotranspiration generates cooling at the forest canopy, but when water vapor condenses into clouds, it releases the heat. Fine; then you could say that there is no overall heating or cooling, right? After all, the 1st principle must be satisfied.

Indeed, it does. When heat is released high up in the atmosphere, it appears mainly in the form of excited vibrational states, which then decay by emitting infrared radiation that can be dispersed to space. This radiation has to go through a thinner layer of greenhouse gases than the kind emitted from the ground. Hence, it is absorbed less, and less heat is beamed down back to Earth. The end result is cooling. Nice trick, right? Forests keep pumping heat away from the Earth’s surface when they are active, in summer in the high latitude regions and almost all the time in the equatorial regions.

This mechanism of pumping heat high up in the atmosphere and the associated cooling effect have been known for a long time. The problem is, how important is this effect? In principle, climate models take it into account, but do they do that correctly? We cannot be sure because the climate system is hugely complex, and separating all the factors at play is not easy at all, including the cooling factor generated by the high albedo of the low-height clouds that the forest creates. But it might be important, perhaps comparable to that of the better known and much more studied greenhouse effect generated by CO2.

In any case, when people discuss the cooling effect of forests, the heat pump contribution is rarely mentioned, and forests are normally described as affecting climate only by carbon storage and the albedo (reflection) effect. These two effects partly compensate each other so that the overall effect is not very large. On this basis, some people propose that cutting forests could cool the planet because the albedo of a desert is higher than that of a forest. Understandably, the logging industry is very happy about that, but it may well be a very bad idea if the heat pump effect is taken into account. Cutting down forests might destroy a major cooling factor that controls the planetary temperature. Instead, reforestation might give us a direction for mitigating global warming—a form of “natural geoengineering” that could do a lot to help us while we reduce emissions.

Also, take into account that forests do not just pump water vapor upward; they also pump it horizontally. It is the mechanism of the “biotic pump” that carries water inland from the oceans. It fertilizes the land and stabilizes the climate.

Carrying heat horizontally also has an overall cooling effect if it goes from lower to higher latitudes. Higher latitudes are colder, so they contain less water vapor, and hence, infrared radiation dissipates more easily into space. Again, it is an effect that’s difficult to quantify, but it certainly exists, and it is closely related to the way the ecosystem works.

So, forests give us a big hope to keep the ecosystem healthy, stable, and cool. Just don’t fall into the trap of thinking that it is only a question of planting trees. And into the even worse trap of saying that young trees are better as carbon absorbers, so it is a good idea to cut old forests down. Single trees, just like young forests, can do little to stabilize climate. We need healthy, strong, and mature forests. And onward we go!

To know more:

Role of trees on moisture convergence

On the mechanism of the biotic pump

Thank you Ugo, great summary. I would like to add that the cooling capacity of the forests are by design highest around the equator where much more solar energy comes in than in for instance the boreal forest areas, where the forest design is more geared towards maximizing photosynthesis in a short summer.

As far as I understand, the forest mechanism of “Air Cooling” (lowering the temperature over a huge area) works during the growing season of trees. In the northern hemisphere it is summer. The most solar radiation comes, the air temperature is highest - and it is during this season that forests transpirate, form clouds, additionally attract moisture from the oceans into the continents ("Biotic pump"), which leads to heavy summer precipitation, feeds rivers, etc. Apparently, in the equator zone, or 0-15 degrees South latitude - where the forests of the Amazon, Congo and Indonesia are located, the same “seasonal” peaks occur: when the temperature is highest, then “forest cooling” works.